Lighting Up Tough Parks' Darkness

Michal Czerwonka for The New York Times

by Rebecca Cathcart

July 11, 2009

LOS ANGELES — Harvard Park has been a no-man's land after dark for decades. Its location, at the borders of rival gang turf, has made it more a demilitarized zone than public space since the inception of this city's oldest and most entrenched street gangs. So there was a giddy excitement among the thousand or so South Los Angeles neighbors who came last week to celebrate the park's inclusion in Summer Night Lights, a program designed to combat gang violence by keeping lights on until midnight in some of the city's roughest parks.

One neighbor, Dorothy Poindexter-Bowen, 60, stood in the park on Wednesday amid the sounds of a new life after dark: laughter, the clatter of skateboards and booming bass from nearby speakers.

“I'm taking it in,” Ms. Poindexter-Bowen said. “I'm thinking how nice it feels to be safe in the park at night.”

The program began in a modest incarnation last year, when antigang outreach workers raised almost $1 million in private donations to illuminate eight parks. The lights spread to 16 locations on Wednesday, including Harvard. Even amid dire financial straits, city officials have pledged to match $1.4 million in private donations to finance the lights, along with sports leagues, disc jockeys and food four nights a week in the parks through August.

“These neighborhoods with gang problems don't have a lot of assets,” said the Rev. Jeff Carr, who leads the program. “But there is a school, a park and a rec center. Those are public assets. Let's use those to create social connections that replace gangs.”

In 2008, neighborhoods bordering the eight parks involved saw 86 percent fewer homicides and a 17 percent drop in gang-related violence, according to police crime statistics. Some parks had no homicides for the first summer in years.

The spillover of a national recession and bloated state budget deficit in 2009 means the program must contend with thinner local safety nets, said Mr. Carr, who directs Gang Reduction and Youth Development for Mayor Antonio R. Villaraigosa. Cutbacks by the Los Angeles Unified School District erased most summer school and other nonacademic programs this year, leaving many young people at loose ends.

On Thursday in Boyle Heights, a working-class area east of downtown, Ramon Garcia park was filled with families and clusters of young men and women. The rush of cars from two freeways mixed with the crack of softball bats and music. Groups of young men wearing the same large white T-shirts and long shorts sat on a grassy slope to watch the game. A teenage girl shared a sideways glance with a boy eating hot dogs next to his parents on the lawn.

“People were just waiting for it this summer,” said Miguel Leon, 27, a gang intervention worker. “Last year it took a while to ramp up; now this place is packed.”

Mr. Leon grew up near the park and oversees 10 teenage boys and girls from the neighborhood hired and trained with federal stimulus money to oversee activities at Ramon Garcia this summer. Most are at risk of falling in with gangs, he said.

Gang members are not barred from the parks, Mr. Carr said, and Mr. Leon said some were playing softball on the field that night. Police officers and gang intervention workers will be present in all 16 parks during the eight-week season.

“We're telling them they're welcome as long as they don't cause problems,” he said. “You can rewrite the narrative of your life and your neighborhood. A gang affiliation is not your whole identity. You're also a part of this community.”

“We just said, Stop shooting,” Mr. Carr added. “If you give people a safe pass to and from the park this summer, you're welcome. You're part of this community too, not an appendage.”

That marks a new approach by officials trying to curb gangs in Los Angeles, which has the most gang violence in California, a state with more gangs in its cities and towns than any other, said Paul Seave, director of Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger's Office of Gang and Youth Violence Policy. Even with falling crime rates this year, he said, gang killings still make up almost half of all homicides in Los Angeles. About 30 percent of murders statewide are tied to gangs, he said.

“Until about five years ago, the approach to gang violence in California was largely a law enforcement one,” Mr. Seave said. “But there has been a sea change in the way everyone, particularly law enforcement, thinks. We cannot arrest our way out of this problem.”

Seemingly small steps like filling parks with people can change the behavior that feeds crime patterns, said Marcos Andrade, 18. Mr. Andrade carried his 9-month-old nephew, Maximum, on his shoulders in Ramon Garcia park Thursday.

“I used to stay away and stay at home at night,” he said. “But I'm really not an indoor type. Now we can be here and have support.” Maybe Maximum, he said, “could grow up more free.”

Laura Lomeli, 24, waiting in line for popcorn nearby, agreed. “It's not just for the kids; parents come and get to know each other,” she said. “We start to know who lives next door.”

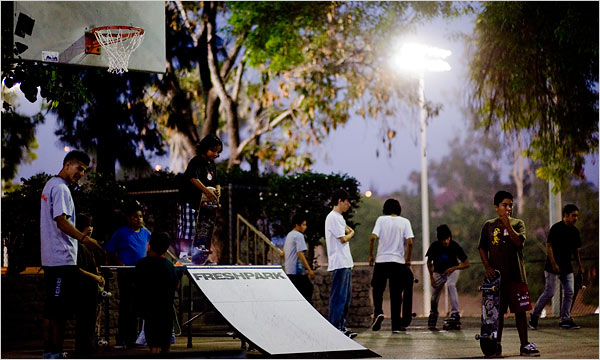

After the softball game ended, two women pushed strollers across the empty field under bright lights. A toddler ran ahead into the shadows. Juan Duran, 13, and Joey Martinez, 16, stood near small skateboard ramps on an outdoor stretch of asphalt.

“My school doesn't have summer school this year,” Juan said. “So it's pretty cool having this.”

“You meet more friends here” than by “having nothing better to do and getting in trouble,” said Joey, one foot on his board. “I always stay here until midnight.”

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/12/us/12park.html?_r=4 |