|

.........

The Afghanistan Surge:

A Logistical Challenge with a Cast of Thousands

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

|

|

The Afghanistan Surge:

A Logistical Challenge with a Cast of Thousands

by David Wood

Politics Daily.com

December 24, 2009

Troops are jamming two dozen at a time into eight-man Arctic tents hastily erected beside the runways at Bagram Air Field in Afghanistan, as the first of the 30,000-plus reinforcements ordered by President Obama arrive for the expanding war.

It's simple enough for the commander in chief to order the additional troops into the fight at "the fastest possible pace,'' as Obama did in his West Point speech Dec. 1. Getting it done, safely and on time, will be barely short of miraculous, given the risks and vulnerabilities involved.

Heavy-lift cargo planes jammed with troops or armored vehicles are lumbering over the rocky peaks that ring Bagram Air Field and into airspace already crowded with jet fighters, unmanned drones, bombers, helicopters and small cargo and passenger jets. Just maneuvering along taxiways overcrowded with parked aircraft and support trucks is a nightmare, pilots say. |

| |

Most (80 percent) of the military cargo headed into Afghanistan goes by land, squeezing through one of five major bridges or mountain passes and along roads made treacherous by winter storms, insurgents' attacks, and bandit hijackings.

An incident -- a downed planeload of soldiers, a crucial bridge blown, an insurgent rocket attack that leaves burning cargo planes blocking a single runway -- could derail the entire sequencing of the surge.

"We could lose everything . . . there are a lot of things that could come down,'' said the man at the center of it all, Air Force Gen. Duncan J. McNabb. He heads the U.S. Transportation Command and is responsible for all movement of military people and equipment worldwide, by air and sea. Right now, his focus is on Afghanistan and what he worries about is "a catastrophic failure.''

So far, McNabb told reporters earlier this month, things are flowing okay. "But I basically would like to have at least double the capacity that we need. Now we don't have all of that in place, but that's kind of where I'd like to be.''

Part of the problem is the flow itself. U.S. military facilities, from air bases to remote Forward Operating Bases (FOBs), were tight a year ago, before Obama took office, when there were only some 30,000 American troops in Afghanistan. By next summer there will be three times that many. But already, the primitive country is starting to resemble a crowded department store where shoppers are getting off of escalators faster than the aisles can absorb them, creating angry bottlenecks.

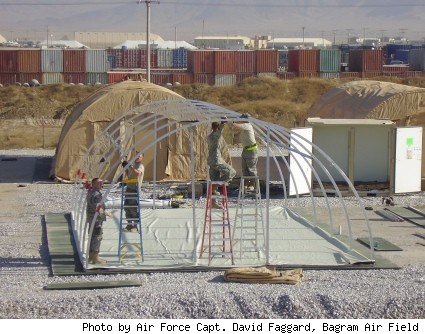

Engineering crews are working at Bagram and across Afghanistan to expand runways, aircraft parking areas, cargo yards, and to build new FOBs, air strips, and logistics bases. But much of the problem is at Bagram, the former Soviet air base that now serves as the United States' main operating hub in Afghanistan.

There, the heated tents going up beside the runway are only one sign of growing strain. Already, Bagram is handling up to 2,000 inbound and outbound troops a day, and just recently loaded 925 tons of cargo in one day, up from about 400 tons a day last summer.

"Every square inch of this air base is utilized,'' Air Force Maj. Jack Elston told me by phone. "Bed spaces are coveted. When your replacement gets here, he gets your bed and you've got to go someplace else.''

Elston is operations officer for an expeditionary civil engineering squadron at Bagram, responsible for building space for airplanes, cargo and people. Even before the surge gets fully underway, "we are at max capacity,'' he said. "We're trying to bring in new airplanes and there's no place to put 'em.''

Bagram's vast acres of concrete look accommodating, but can hold only so many aircraft. That limit is known as the Maximum on Ground, or MOG. Once it's reached, a red flag goes up on computer screens at the Tanker Airlift Control Center at Scott Air Force Base in Illinois. " Bagram's mogged out,'' an operator will announce, and inbound flights start getting diverted like passenger jets from an O'Hare snowstorm.

Afghanistan is a big and mostly empty place. But simply expanding out into the desert is not an easy option. "Before you use any land, it has to be de-mined,'' Elston said, cleared of the land mines buried by Russians and warlords and insurgents over at least three decades of war. De-mining is mostly done by Afghans hired to gently probe the ground with sticks. I've also seen it done at Bagram by brute force, with a huge armored bulldozer just plowing up the dirt and taking an occasional clanging hit.

Other frustrations: Afghans hired for construction work often quit because the risks of working with Americans outweigh steady wages, Elston said. Getting construction material delivered is difficult because trucks can get hijacked and containers stolen or pirated, he said.

One project at Bagram is installing relocatable buildings, basically steel shipping containers that are stacked and welded and hooked up to power and ventilation and used as offices and living quarters. The buildings require land to be cleared and foundations to be built, and the effort is six months behind.

"Part of our mission is to help the Afghans learn construction, so projects take a lot more guidance and take a lot of attempts before they get finished,'' Elston said. "It's frustrating because we need these facilities right away.''

Getting the stuff into Afghanistan remains the larger problem. McNabb's staff is working on four innovations to help ease the strain:

-- They have begun using Boeing's huge 747-400 freightliners to airlift M-ATVs, the new armored vehicles built for Afghanistan directly from Charleston S.C., where the vehicles are finished, nonstop right into Afghanistan. Each 747 carries five M-ATVs. That's more expensive than shipping them by sea, but an enormous saving of time.

-- Instead of flying the normal route from Charleston Air Force Base to Germany and on into Bagram, what about flying over the North Pole and south across Russia, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan right into Bagram, a much shorter distance? McNabb has already held two demo flights over Russia and discussions are underway to make a regular polar route possible. One problem: that's the same trajectory that intercontinental ballistic missiles would take in a nuclear war between the U.S. and Russia.

-- Increasing air drops. Some of the cargo, rigged to parachutes, can be shoved out the back of C-130 cargo planes, as I wrote about last summer. That takes the load off hubs like Bagram, and means fewer truck convoys on the roads.

-- Most intriguing, McNabb's team is experimenting with unmanned cargo aircraft that could pick up and deliver small but valuable cargo. Unmanned aircraft would remove air cargo crews from the risks of flying into ongoing firefights, as they sometimes do now. No word on whether the experimental craft will be ready in time to serve in the surge. |

|

|

|

|

|