It also revived interest in the KKK, leading to the birth of several new local groups that summer and fall. Many more followed, mostly in southern states at first. Some of these groups focused on supporting the U.S. effort in World War I, but most wallowed in a toxic mix of secrecy, racism, and violence.

As the Klan grew, it attracted the attention of the young Bureau. Created just a few years earlier—in July 1908—the Bureau of Investigation (as the organization was known then) had few federal laws to combat the KKK in these formative days. Cross burnings and lynchings, for example, were local issues. But under its general domestic security responsibilities, the Bureau was able to start gathering information and intelligence on the Klan and its activities. And wherever possible, we looked for federal violations and shared information with state and local law enforcement for its cases. Our early files show that Bureau cases and intelligence efforts were already beginning to mount in the years before 1920. A few examples:

In Birmingham, a middle-aged African-American—who fled north to avoid serving in the war—was arrested for draft dodging in May 1918 when he returned to persuade his white teenage girlfriend to marry him. A Bureau agent looking into the matter discovered that the local KKK had gotten wind of the interracial affair and was organizing to lynch the man. The agent came up with a novel solution to resolve the draft-dodging issue and to protect the man from harm: he escorted the evader to a military camp and ensured that he was quickly inducted. In Birmingham, a middle-aged African-American—who fled north to avoid serving in the war—was arrested for draft dodging in May 1918 when he returned to persuade his white teenage girlfriend to marry him. A Bureau agent looking into the matter discovered that the local KKK had gotten wind of the interracial affair and was organizing to lynch the man. The agent came up with a novel solution to resolve the draft-dodging issue and to protect the man from harm: he escorted the evader to a military camp and ensured that he was quickly inducted.

In June 1918, a Mobile agent named G.C. Outlaw learned that Ed Rhone—the leader of an African-American group called the Knights of Labor—was worried by the abduction of another labor leader by reputed Klansmen. “This uneasiness of the Knights of Labor,” our agent noted, “is the first direct result of the Ku Klux activities.” Agent Outlaw investigated and assured Rhone we would protect him from any possible harm. In June 1918, a Mobile agent named G.C. Outlaw learned that Ed Rhone—the leader of an African-American group called the Knights of Labor—was worried by the abduction of another labor leader by reputed Klansmen. “This uneasiness of the Knights of Labor,” our agent noted, “is the first direct result of the Ku Klux activities.” Agent Outlaw investigated and assured Rhone we would protect him from any possible harm.

At the request of a Bureau agent in Tampa, a representative of the American Protective League—a group of citizen volunteers who helped investigate domestic issues like draft evasion during World War I—convinced an area Klan group to disband in August 1918. At the request of a Bureau agent in Tampa, a representative of the American Protective League—a group of citizen volunteers who helped investigate domestic issues like draft evasion during World War I—convinced an area Klan group to disband in August 1918. |

World War I effectively came to an end with the signing of a ceasefire in November 1918, but the KKK was just getting started. Pro-war oriented Klan groups either folded or began to coalesce around a focus on racial and religious prejudice. Teaming up with advertising executive Edward Young Clarke, the head of the Atlanta Klan—William Simmons—would oversee a rapid rise in KKK membership in the 1920s.

That’s another story, and one that we will tell as part of this new history series detailing the work of the FBI to protect the American people—especially minorities and other groups—from the evils of the modern-day Klan. Over the course of the year, we will track the major aspects of this fight, with new documents and pictures to help tell the tale. Stay tuned.

http://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/2010/february/the-fbi-versus-the-klan-part-1/the-fbi-versus-the-klan-part-1-let-the-investigations-begin

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

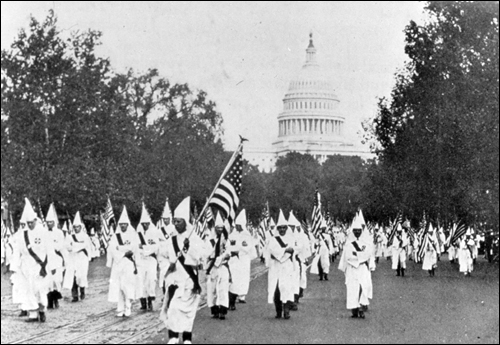

The KKK marches down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C. in 1925.

In the mid 20s the Klan boasted several million members and had

become a clear threat to public safety, law and order. |

|

The FBI Versus the Klan

Part 2: Trouble in the 1920s

April 29, 2010

The Roaring Twenties were a heady time, full of innovation and exploration—from the novelty of “talking pictures” to the utility of mass-produced Model Ts...from the distinct jazz sounds of Duke Ellington to the calculated social rebellion of the “flappers”...from the pioneering flights of Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart to the pioneering prose of F. Scott Fitzgerald and William Faulkner.

It was also a lawless decade—an age of highly violent and well-heeled gangsters and racketeers who fueled a growing underworld of crime and corruption. Al Capone and his archrival Bugs Moran had formed powerful, warring criminal enterprises that ruled the streets of Chicago, while the early Mafia was crystallizing in New York and other cities, running various gambling, bootlegging, and other illegal operations.

Contributing to criminal chaos of the 1920s was the sudden rise of the Ku Klux Klan, or KKK. In the early 1920s, membership in the KKK quickly escalated to six figures under the leadership of “Colonel” William Simmons and advertising guru Edward Young Clarke. |

By the middle of the decade, the group boasted several million members. The crimes committed in the name of its bigoted beliefs were despicable—hangings, floggings, mutilations, tarring and featherings, kidnappings, brandings by acid, along with a new intimidation tactic, cross-burnings. The Klan had become a clear threat to public safety and order.

Matters were getting so out of hand in the state of Louisiana that Governor John M. Parker petitioned the federal government for help. In a memo dated September 25, 1922, J. Edgar Hoover—then assistant director of the Bureau—informed Director Burns that a reporter had brought a personal letter from Parker to the Department of Justice. “The Governor has been unable to use either the mails, telegraph, or telephone because of interference by the Klan … Conditions have been brought to a head at Mer Rouge, when two white men … were done away with mysteriously,” Hoover wrote. He also said that the governor was seeking assistance because “local authorities are absolutely inactive” and because he feared judges and prosecuting attorneys had been corrupted.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Read the Memos:

Sept. 25, 1922

Nov. 13, 1922

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Department responded, immediately sending four Bureau agents—A. E. Farland, J. D. Rooney, J. P. Huddleston, and W. M. Arkens—to work with the Louisiana attorney general to gather evidence of state and federal crimes. The agents soon found the bodies of the two men and pinpointed members of the vigilante mob that kidnapped and brutally murdered them. They also identified the mob’s leader—Dr. B.M. McKoin, the former mayor of Mer Rouge

The agents' work put their own lives in danger. On November 13, 1922, an FBI Headquarters memo noted that “confirmation has just been received of the organized attempt of klansmen and their friends to arrest, kidnap, and do away with special agents of the Department who were in Mer Rouge.” To make matters worse, the plot was “stimulated by the United States Attorney at Shreveport,” reportedly an active KKK member. The U.S. attorney had already ordered the investigating agents, detailed from the Houston Division, to leave the area or be arrested because he thought they had no business investigating those matters. “Only their hurried exit saved them,” the memo said. Still, the agents continued their work.

In 1923, McKoin was arrested and charged with the murders of the two men. Despite National Guard security, witnesses were kidnapped by the Klan, and other attempts were made to sabotage the trial. The grand jury refused to return an indictment. Other KKK members, though, ended up paying fines or being sentenced to short jail terms for miscellaneous misdemeanors related to the murders.

Despite the Bureau’s work, the power of the KKK in certain places was too strong to crack. But as revelations of leadership scandals spread and figures like Edward Young Clarke went to jail, the Klan’s membership dropped off precipitously. By the end of the decade, thanks in part to the Bureau, the KKK had faded into the background—at least for a time.

http://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/2010/april/klan2_042910

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

KKK cross burning

|

|

The FBI Versus the Klan

Part 3: Standing Tall in Mississippi

October 29, 2010

As the civil rights movement began to take shape in the 1950s, its important work was often met with opposition—and more significantly, with violence—by the increasingly resurgent white supremacists groups of the KKK.

FBI agents in our southern field offices were on the front lines of this battle, working to see that the guilty were brought to justice and to undermine the efforts of the Klan in states like Mississippi. |

That was often difficult given the reluctance of witnesses to come forward and testify in court and the unwillingness of juries to convict Klansmen even in the face of clear evidence.

Fortunately, the struggles and insights of many of these agents have been recorded for posterity, and transcripts are available for review by the general public—thanks to the Society of Former Special Agents of the FBI and the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Foundation, which broke ground on a museum earlier this month.

In this story and the next in our Klan series, we’ll highlight a few of these memorable discussions with our agents concerning their work against the KKK. The first comes from FBI Agent James Ingram, who served from 1957 to 1982 and played a key role in many civil rights investigations. Agent Ingram, who died recently, was assigned to the newly opened Jackson Field Office in Mississippi in 1964. A retired agent and colleague in Jackson, Avery Rollins, interviewed Ingram before his death:

Special Agent Rollins: “You said that your average work week was six-and-a-half days. I would assume that your average work day was anywhere from 10 to 12 hours long?”

Special Agent Ingram: “Oh, it was. …That’s why we defeated the Klan. … there was never a defeatist attitude because we were all on the same schedule. And everyone knew that we had to work.”

That work continued following passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964:

Special Agent Ingram: “There was one thing about [the law], Mr. Hoover knew that it was important. He gave Inspector Joe Sullivan and [Jackson Special Agent in Charge] Roy Moore a mandate. And he said, ‘You will do whatever it takes to defeat the Klan, and you will do whatever it takes to bring law and order back to Mississippi.’”

The threats to FBI agents were real:

“Agents would always watch. They’d look underneath their cars to make sure we did not have any dynamite strapped underneath … Then you’d open your hood and make sure that everything was clear there. We had snakes placed in mailboxes. We had threats.”

But using informants and other tools, the tide began to turn:

“[W]e infiltrated the Klan in many ways. We had female informants. … And we had police officers that were informants for us.”

“When you look back, the FBI can be proud that they stopped the violence [of the KKK]. We had the convictions. We did what we had to do from Selma, Alabama to Jackson, Mississippi to Atlanta, Georgia."

In the words of Special Agent Rollins, “…the FBI broke the back of the Klan in Mississippi. And eradicated it…”

A complete transcript of the interview of James Ingram can be found on the

National Law Enforcement Officer Memorial Foundation Museum website, including much more discussion on the Klan. Also see additional FBI oral histories.

Resources:

- Retired Agent Revisiting Cold Cases Resources:

- Retired Agent Revisiting Cold Cases

http://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/2010/october/kkk_102910/kkk_102910

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

FBI History website

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ |